Child Rights Impact Assessments (CRIA) – Ex ante

ContentsConducting a CRIA

- A CRIA generally involves a series of steps laid out in a formal model or template to evaluate the impacts of a proposed change to policy or legislation.

- Overall, the process aims to answer these central questions:

- what are the potential impacts of a proposed legislation on children’s rights?

- what changes in the proposed legislation are required to better protect and promote children’s rights?

- There is no single prescribed method to follow when conducting a CRIA, and many States Parties have developed their own approach appropriate to their context.

- Generally, a CRIA process involves the following core elements (Corrigan 2006; Mason and Hanna 2009; UNICEF 2013):

- A SET OF CORE QUESTIONS

- SCREENING/INITIAL ASSESSMENT STAGE

- SCOPING

- DATA COLLECTION, EVIDENCE GATHERING, AND CONSULTATION

- IMPACT ASSESSMENT

- LIST OPTIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

- REPORTING

- MONITORING AND EVALUATION

A SET OF CORE QUESTIONS

- A coherent set of key questions guides people through the impact assessment process and ensures that the CRIA follows a CRBA.

- See for example CRIA Template - Commissioner for Children and Young People (Northern Ireland)

SCREENING/INITIAL ASSESSMENT STAGE

- The screening or filtering process in the initial stage is common to most impact assessment procedures. It will help to determine the scope of CRIA, also in light of the method of legislative reform (see earlier above > Incorporation > methods).

- At this stage it should be decided who will conduct the CRIA. This role is generally referred to as the CRIA Assessor(s).

Specialist expertise of a CRIA Assessor

Expertise includes:

- Knowledge on children’s rights, the CRC and other relevant international instruments.

- Professional experience working with children or experience with the practical effects of the legislation’s implementation on children's lives and environment.

- Specialised knowledge and experience with the technical aspects of drafting and implementing legislation.

- Any other specialised knowledge related to the issues to be considered.

- It is unlikely that one person will have expertise in all relevant areas. Therefore, the analysis can be conducted by an expert team drawn from government (and possibly also other stakeholders, including NGOs or academic institutions; see also WHO).

- The inclusion of diverse viewpoints should be encouraged, promoting a comprehensive understanding of the effect of the legislation on children and the range of possible recommendations.

- Some States Parties maintain permanent legal or law reform commissions which regularly review all legislation and make recommendations for legislative reform as necessary. For a specific analysis of legislation relating to children's rights, such a general commission could be augmented by child rights specialists.

- Some States Parties may take a more restricted approach, hiring a team of legal experts as consultants to undertake an assessment of laws relating to children’s rights.

- This approach may involve the following disadvantages:

- Although such experts may have extensive legal knowledge, they can lack experience in the actual implementation of the legislation and knowledge of the contextual situation.

- As a result, their analysis may be less complete than it might be with a broader group of experts.

- The personal ideas and expectations of the consultants may bias the analysis in some direction because they would lack the wider perspective of a more diverse expert panel.

- Finally, this stage (and the following stages) requires documentation of the decisions made, signed off by the authority which is managing the CRIA assessor(s).

SCOPING

- In the scoping phase, the CRIA assessor(s) should identify the information (such as laws, policies, research) that will be scrutinised at the impact assessment stage.

- Scoping helps to identify the information that is already available to the CRIA assessor and determine what still needs to be collected to complete the CRIA.

- With the CRIA following a CRBA, the scoping stage promotes collaboration across departments and disciplines and supports the development of a more accurate and comprehensive CRIA. It can identify occasions when it would be useful to involve experts from outside government.

- It should also highlight which children’s rights are most likely to be affected to guide the evidence-gathering and impact assessment portions of the CRIA process.

- Scoping should take into account:

- the extent to which the new/proposed legislation gives effect to specific provisions of the CRC and its key principles (see also under Incorporation and the WHAT section).

- the ways in which that legislation directly and indirectly affects children's rights.

- In the scoping phase, the coordination and the management of the CRIA process should be clearly worked out.

- Additionally, scoping should identify and list the other relevant incorporation measures (legal and non-legal), including budgeting.

DATA COLLECTION, EVIDENCE GATHERING, AND CONSULTATION

- Both quantitative and qualitative data should be used in the CRIA process. This requires identifying key missing information/evidence that is beneficial in the analysis.

- In some legal systems all relevant pieces of legislation may not be available in one catalogue, in which case a compilation will be needed as a first step.

- In terms of legislation:

- Legislation requiring analysis can be divided into three categories:

- Legislation at the national level that deals directly with matters affecting children’s rights.

- Legislation at the national level which does not refer specifically to children but has an impact on them and their rights.

- Legislation at other levels of government that has an impact on children's rights.

- The data collection/evidence gathering may require an understanding of customary rules and jurisprudence gained by interviewing traditional leaders or others who administer customary law if such information is not otherwise available.

- Legislation requiring analysis can be divided into three categories:

- It is also advisable to leverage academic or professional expertise, particularly in cases where there is a lack of readily available published research that can assist in the Impact Assessment stage.

- It is also recommended that consultations be conducted with key stakeholders on significant or substantial policies. CRIAs should ensure that children’s views and experiences are gathered, included and recorded, and clearly indicate how these views have informed the child rights analysis and the conclusions/recommendations. See also section Ensure a participatory and inclusive process.

IMPACT ASSESSMENT

- Once the proposal has been clearly defined, and relevant evidence has been gathered and thoroughly analysed, it is time to assess its impact on children’s rights. This final assessment phase is the culmination of preceding stages.

- The impact assessment should indicate whether the evaluated impact(s) are positive, contributing to the advancement of children's rights; neutral, suggesting no significant change expected either way; or negative, indicating the necessity for policy modification or mitigation of anticipated effects.

- Assessors should provide a clear rationale for categorising the impact as positive, neutral or negative.

- The impact assessment requires going beyond assessing the text of a law and including an examination of how legislation is applied and interpreted by the courts and by the authorities responsible for its implementation. It will have to address conflicts between law in the books and law in action.

- Furthermore, the impact assessment may highlight whether the anticipated impact of the proposal will manifest in the short, medium or long term.

- Given that impacts can vary among different groups of children, the impact assessment should identify these differential effects and propose strategies for addressing the competing interests of these groups effectively.

- The assessment generally focuses on positive impacts that will help progress children’s rights, or negative impacts that will require modification of the law or policy, or mitigation of its anticipated effects.

- Additional factors that can be considered include:

- the likelihood of the impact;

- the severity of the impact;

- the level of vulnerability of the children affected;

- the level of significance that different groups place on the impact;

- the number of children affected; and/or

- how the competing interests of different groups of children should be dealt with

- Where possible, the assessment should identify any associated resource implications, as well as the additional measures needed for implementation (legal and otherwise).

- A cost-effective analysis is important at this stage and can be used to make a strong case for the government to take the proposal forward.

E.g.: Costing the South African Child Justice Bill. An important advantage of completing the cost‐effectiveness analysis during the drafting of the Child Justice Bill was that it allowed for revisions. The Bill had been criticised at that stage for requiring magistrates presiding over preliminary inquiries to recuse themselves from a subsequent trial if they had heard any prejudicial evidence during a preliminary inquiry. The critics claimed that this would prove too expensive, and this criticism was used to support calls to amend the bill and remove the requirement for the magistrate to attend the preliminary inquiry. This issue was examined by the economists, and the costs were found to be insignificant, so the magistrate’s attendance at the preliminary inquiry remained part of the Child Justice Bill. The costing analysis also demonstrated the cost‐effectiveness of clustering services. An enabling clause for the establishment of ‘one stop’ centres was added to the draft Child Justice Bill.

Source:REFORMING CHILD LAW IN SOUTH AFRICA: BUDGETING AND IMPLEMENTATION PLANNING UNICEF 2009.LIST OPTIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

- The outcome of the impact assessment stage should be used to draw up recommendations, which affect the content of the legislative proposals as well as the implementation strategies needed.

- The conclusions and recommendations of the CRIA must be owned by all those who will have a responsibility in the drafting as well as the necessary follow-up. This includes not only the government, but also the other actors involved (see WHO).

- Ensuring full government ownership – from the beginning, representatives of key ministries should be involved in the analysis of existing legislation and in formulating any recommendations about changes that may be needed, including decisions about budgetary and administrative resources to support the implementation of existing legislation and any new measures that may be proposed.

- Ensuring ownership of outcomes by professionals, stakeholders and the general public – this involves creating opportunities for stakeholders and others to meaningfully engage throughout the CRIA process.

- When negative impact is identified, the impact assessment should list concrete alternatives to the proposal being considered and their projected impacts.

REPORTING

- A summary report should be written in easily accessible language for distribution in physical and electronic format, including through traditional media, social media and at public events.

- A child-friendly version of the report should also be made available.

- Disseminating the analysis can provide opportunities for public debate involving children.

- The conclusions of the CRIA should address the identified inadequacies or gaps by suggesting possible changes in the legislative proposal and administrative measures that could be taken.

- Concrete suggestions to overcome the potential limitations of the State Party’s ability to implement the CRC should be included in the recommendations.

- Stakeholders responsible for following up and implementing the recommendations should be clearly identified, as well as a timeline and resources needed.

- The recommendations should be as specific as possible to guide subsequent governmental actions, including the drafting of new or revised legislation as well as any related policies, administrative arrangements or budgetary provisions that may need changes.

- A child friendly version of the final document should also be published in local languages.

- The document should also clearly outline how the contributions of community actors (including children) have been taken into account.

MONITORING AND EVALUATION OF THE CRIA PROCESS

- Ideally, CRIA is an ongoing and iterative process. Building in a monitoring and review process is important to ensure that the original policy aims are met, while respecting, protecting and fulfilling children’s rights affected by those policies/measures.

- Monitoring the CRIA process itself is important to show its effectiveness.

- Monitoring of the CRIA is not to be confused with evaluation and monitoring of legislation.

- In State Parties where CRIA is embedded in law and or policy, there is a growing interest in using an ex-post analysis in some jurisdictions (UNICEF UK, 2017).

See also

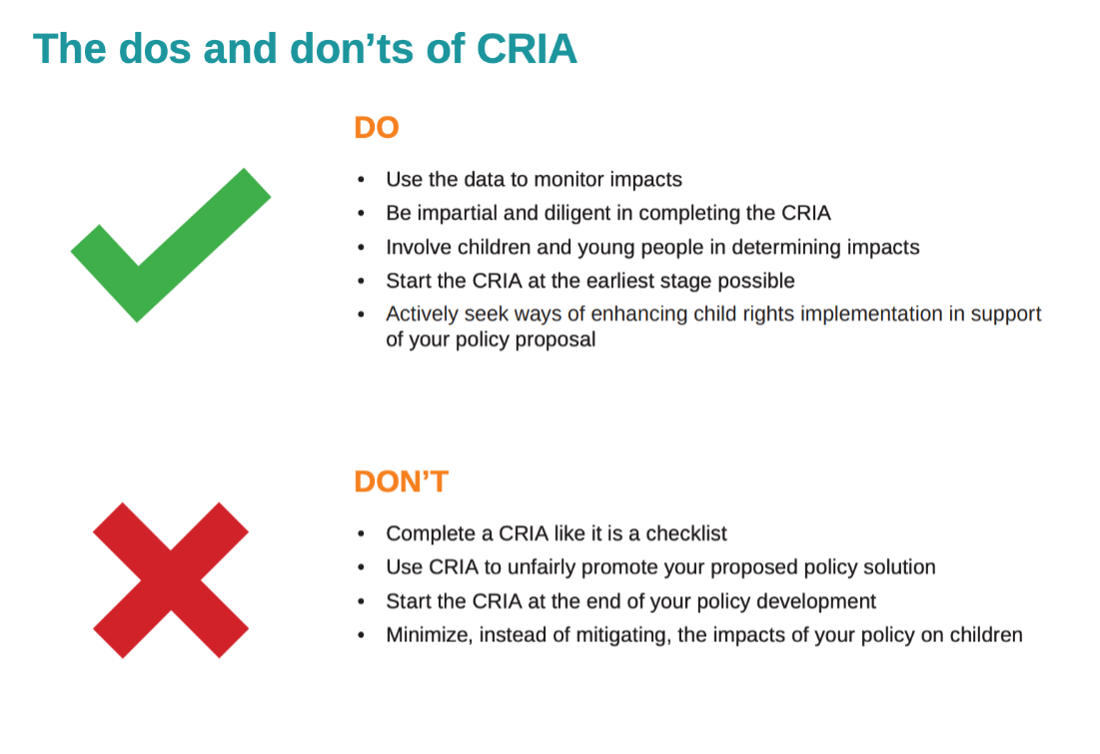

The effectiveness of CRIA is dependent on certain elements of good practice being recognised and applied in the development and delivery of the CRIA model in use:

- Setting out a clear purpose for CRIA

- Making it mandatory with a clear material scope

- Securing support at senior levels of government

- Incorporating human and financial resources needed for the legislative reform and subsequent implementation.

- Beginning CRIA as early as possible in the legislative reform process

- Using a template and guidance to ensure consistency in CRIAs

- Providing training and support on CRIA and the CRC

- Ensuring availability of up-to-date, comprehensive and reliable data

- Ensuring that children’s views and experiences inform the CRIA

- Opening up the process to external scrutiny through stakeholder involvement and publication

Other Examples and Tools:

- CHILD RIGHTS IMPACT ASSESSMENT (CRIA) WORKSHEET (UNICEF Canada)

- Children’s Rights Impact Assessment – Scotland's Commissioner for Children and Young People

- Integrating a Child Focus into Poverty and Social Impact Analysis (PSIA): A UNICEF-World Bank Guidance Note (2011)

- Ex-ante Analysis of the Impact of Proposed Taxation Changes on Vulnerable Children and Families in Serbia (2010)

- Bosnia and Herzegovina: Child Rights Impact Assessment of Economic Policies (2007-2008)

- Bill S-203: Protecting Young Persons from Exposure to Pornography Canada CRIA

- Conversion Therapy Bill Canada CRIA

- Common Framework of Reference on Child Rights Impact Assessment A Guide on How to carry out CRIA, European Network of Ombudspersons for Children (2020)