Key elements of a Children's Rights Based Approach to legislative reform

Contents- The CRC Framework

- Wider Framework for Children’s Rights

-

Key elements of a Children's Rights Based Approach to legislative reform

- Definition of the child

- Universality of rights

- Interrelatedness, interdependence and indivisibility of rights

- Recognition of children as rights holders

- Non-discrimination and equality before the law

- Best interests of the child

- Participation and the right to be heard

- Right to life, survival and development

- Evolving capacities of the child and the role of parents

- Accountability - Access to justice and effective remedies

- The legal context for implementation of international law

Participation and the right to be heard

Background

Participation of all stakeholders

Participation of stakeholders is one of the essential attributes of a human rights-based approach, and must guide children’s rights legislative reform.

Children form an essential group of stakeholders with the right to participate.

Participation of children as a right

According to article 12(1) CRC, States Parties must ensure that children capable of forming their own views have the right to express those views freely in all matters affecting them, and that due weight be given to these views in accordance with their age and maturity.

This right highlights the role of the child as an active participant in the promotion, protection and monitoring of their rights (CRC GC 12, para. 12).

The right “imposes a clear legal obligation on States Parties to recognise this right and ensure its implementation by adopting or revising laws” (Sloth-Nielsen & Oliel 2019, p. 14 with reference to CRC GC 5, para. 12).

- Article 12 CRC does not limit this right by age. The right also applies to young children, whose views should also be heard and taken into account (CRC G C 7, para. 14). The CRC Committee discourages States from imposing age limits in law or in practice on children’s rights to be heard in all matters affecting them (CRC GC 12, para. 21).

- The right to be heard is sometimes neglected in national legislation, because of the prevalence of views on children as objects of adults’ goodwill rather than rights holders.

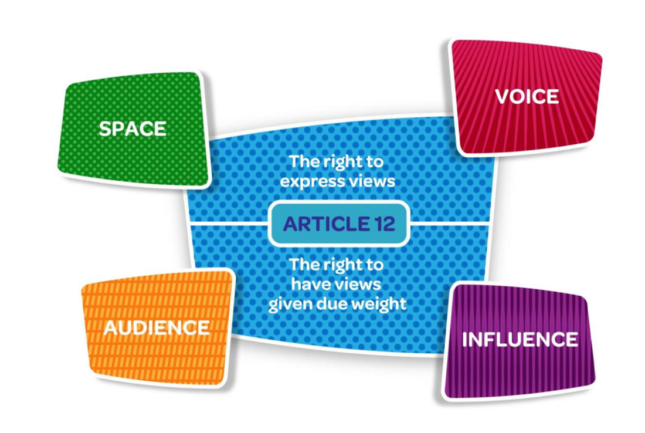

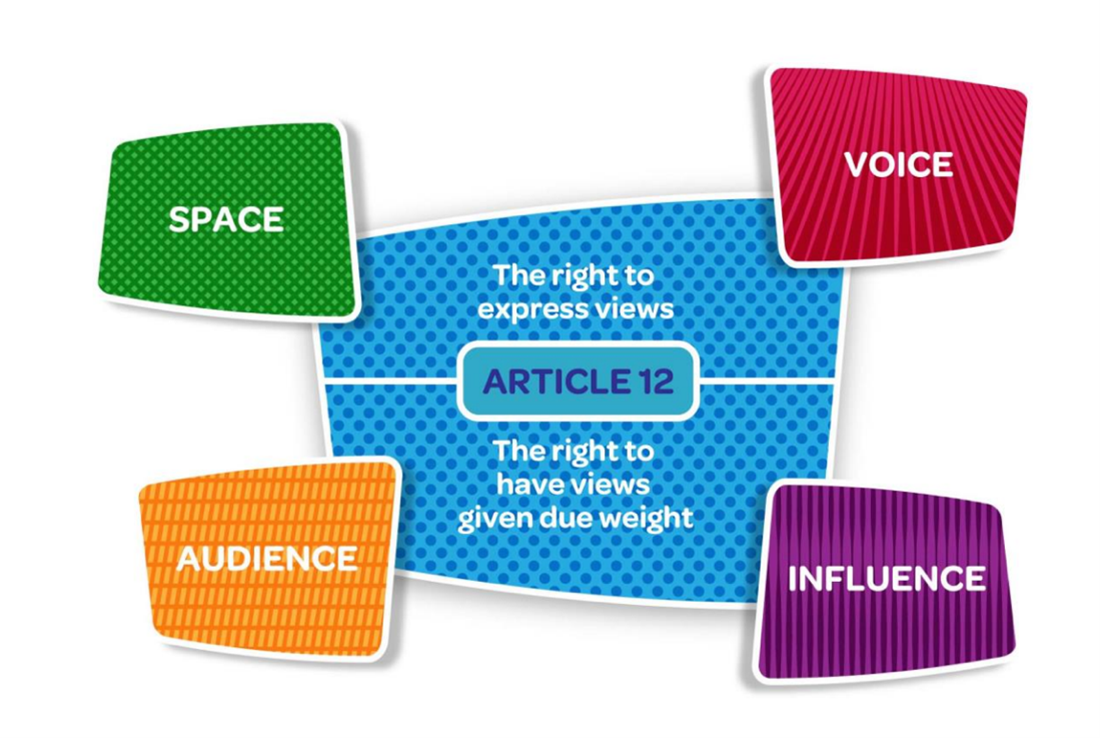

- The Lundy model of child participation identifies four elements for child participation: space, voice, audience and influence (Lundy 2007).

- Space: safe and inclusive opportunities for children to form and express their views

- Voice: children must be facilitated to express their views

- Audience: listening to the views of children

- Influence: acting upon the views as appropriate

Implications for legislative reform

In the legislative reform process

Legislative reform should be conducted in a participatory manner, paying particular attention to the views of children, from various backgrounds, at all stages.

The legislative reform process must be inclusive and adapted to allow all children, including vulnerable or marginalised children, to take part.

- This requires States Parties to provide education and awareness on human rights and children’s rights, and legislation in general.

- Article 42 CRC provides that States Parties must make the principles and provisions of the CRC widely known, by appropriate and active means, to adults and children.

- For example, see WHO section > Other community actors > Children; and HOW section > Ensuring a participatory and inclusive process - Consultations.

In the substance of the legislation

An express provision for children’s right to be heard should be included in the legislation.

It is recommended, as a minimum, to use the text of article 12 CRC.

In Zambia, Section 6 of the Children’s Code 2022 provides that “A child who is capable of forming that child’s own views shall be informed of, and be accorded an opportunity to express that child’s opinion in a decision or a matter of procedure affecting the child, and that opinion shall be taken into account, as may be appropriate, having regard to the age and maturity of the child and the nature of the decision.”

States Parties can also protect children’s right to be heard in their Constitutions.

E.g.: Article 104 of the Constitution of the Kingdom of Norway provides that children “have the right to be heard in questions that concern them, and due weight shall be attached to their views in accordance with their age and development”. The Constitution of the Kingdom of Norway uses wording similar to that in article 12 CRC. See Trude Haugli et al. (2020).

E.g.: Article 59.V of the Constitution of Bolivia provides that “The State and society guarantee the protection, promotion and active participation of youth in productive, political, social, economic and cultural development, without any discrimination whatsoever, in accordance with the law”. This implies that youth (and presumably children) in Bolivia have a right to participate that must be guaranteed by both the State and society.

Some States do not have child-specific provisions on the right to be heard, but have legal provisions that relate to children’s (political) participation.

Under the provisions on “Political Rights” of its Constitution, Brazil has included a constitutional provision which makes it possible for children aged between 16 and 18 years to exercise the constitutional option to vote (article 14 II (c)).

In addition to including the right to be heard in legislation, domestic legislation should provide specific structures to enable child participation in decision-making at a local and national government level. This could for example relate to the establishment of school councils and Children’s Parliaments. Such structures could subsequently feed back into children’s rights legislative reform.

E.g.: Scotland established a Children’s Parliament in 1996. It provides children from diverse backgrounds across Scotland with opportunities to share their experiences, thoughts and feelings in order to bring about positive change in their lives. The work of the Children’s Parliament supports the Scottish Government, local authorities and other public bodies to fulfil their legal obligations to promote and protect human rights and fulfil their duty of care towards children. As part of the public consultation on the incorporation of the CRC into domestic law in Scotland, the Children’s Parliament delivered workshops to explore children’s experiences, views and ideas on the incorporation of the CRC, embedding rights in public services, and redress for rights violations.

E.g.: Ireland developed a National Strategy on Children and Young People’s Participation in Decision-Making (2015-2020). The Strategy identified the following objectives and priority areas for action:

- 1. Children and young people will have a voice in decisions made in their local communities.

- 2. Children and young people will have a voice in decision-making in early education, schools and the wider formal and non-formal education systems.

- 3. Children and young people will have a voice in decisions that affect their health and well-being, including on health and social services delivered to them.

- 4. Children and young people will have a voice in the Courts and legal system.

At the national level, this Strategy was supported by a number of infrastructures that support or directly give children and young people a voice, such as the National youth parliament (Dáil na nÓg), Local youth councils (Comhairle na nÓg), or Student councils.